JIT-ing a stack machine (with SLJIT)

From bytebeat to JIT

Recently, I got nerdsniped with bytebeat. I made a simple program for editting it live with visualization 1. Then I found the expression language quite limted and started making extensions. Half way through, I realized it could just be a “real programming language” ™ which could be edit in a “real text editor” and get hot reloaded on change.

Since I already have that, a new version was developed. It looks something like this:

A long the way, I noticed that the CPU usage was a bit high. While it is nothing my monster of a desktop can’t handle, it would be a problem on smaller devices 2. So I finally have an execuse to explore JIT compilation. And this is the result.

While this post is about JIT’ing the uxn machine, a VM for a stack-based language, a lot of techniques are transferable to other languages. After all, many languages also target a stack machine under the hood.

The plan

Currently, to execute any bytecode, I’d call: buxn_vm_execute.

If JIT is truly magic, it should be a drop-in replacement: buxn_jit_execute.

Just like everything else, I have never written a JIT compiler before but intuitively, it should work like this:

- Check if the current entrypoint has been JIT’ed before. If it has, just run the JIT’ed version. Otherwise, continue.

- Statically trace the execution of the current code block. This will help identify which range of bytecode needs to be JIT’ed.

- JIT it with sljit. This is chosen because it looks simple to use and integrate: Just one header and one source file 3. At that moment in the project, I had no idea how to transform stack code into SSA either 4. SLJIT allows me to write “portable assembly” which I am already familiar with.

- Put the JIT’ed code in the cache of step 1.

This is what one would call a “method JIT”. The tracing is actually done statically.

A quick primer on sljit

It is a fairly simple library to use with an excellent tutorial series and documentation. But here’s the gist of it:

- One would call

sljit_emit_enterto start a function. -

There are various

sljit_emit_xfunctions to emit portable assembly instructions. They are just about one would expects: arithmetic, branching, memory load/store… The API resembles x86 5 somewhat with various addressing modes. An operand can be:- An immediate value (like a constant)

- A value loaded from a register (like local a variable)

- A value loaded from memory, using a register as an address (like dereferencing a pointer)

- A value loaded from memory, using one register as a base and another as an index (like using an array)

-

Instead of using the actual register names, we use the virtual SLJIT register names like

SLJIT_S0,SLJIT_R0,SLJIT_S1,SLJIT_R1… The registers are divided into:- Saved registers, whose names start with

SlikeSLJIT_S0. They keep their values between function calls. - Scratch registrs, whose names start with

RlikeSLJIT_R0. They have undefined values between function calls.

We don’t have to worry about what is caller-saved or callee-saved in various calling conventions as SLJIT will deal with that. SLJIT will also automatically map hardware register to those virtual registers depending on the platform.

- Saved registers, whose names start with

-

For branching:

- Jump emitting functions (e.g:

sljit_emit_jump) return asljit_jump*pointer. At this point the jump target is not yet defined. sljit_emit_labelreturns asljit_label*pointer. The label points at the current position in the code stream.sljit_set_label(jump, label)connects a jump to a label. This allows a jump to target either a previous label or a label defined later since the connection does not have to be done immediately 6.

- Jump emitting functions (e.g:

- Finally,

sljit_emit_returnwraps up the function andsljit_generate_codereturns a function pointer that C code can just call like a regular function.

The wrinkles

How many registers to use?

Immediately, sljit_emit_enter asks us how many scratch and save registers to use.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

The pointer to current VM instance should be saved, I guess. And the stack pointers too. But I have a feeling the numbers will keep changing and I’ll have to update several parts in the code. So I use one of the oldest trick in the book 7: counting enum.

// Saved registers

enum {

BUXN_JIT_S_VM = 0,

BUXN_JIT_S_WSP,

BUXN_JIT_S_RSP,

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

};

// Scratch register

enum {

BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE = 0,

BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET,

BUXN_JIT_R_TMP,

// More registers

// ...

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

};

We can refer to a saved register with SLJIT_S(index) like this: SLJIT_S(BUXN_JIT_S_VM).

Same for scratch registers: SLJIT(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE).

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT and BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT always count the correct number of registers.

How to address memory on x86-32?

SLJIT contains this scary note:

Note: on x86-32, S3 - S6 (same as R3 - R6) are emulated (they are allocated on the stack). These registers are called virtual and cannot be used for memory addressing (cannot be part of any SLJIT_MEM1, SLJIT_MEM2 construct). There is no such limitation on other CPUs. See sljit_get_register_index().

I debated a bit about dropping x86-32 as who uses that nowadays?

But in the spirit of permacomputing, it should be supported.

That means accessing memory has to be done through a few number of “blessed” registers: BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE and BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET.

Ideally, we don’t want to keep emitting the same BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE adjusting instruction again and again.

Its last position should be saved in the compiler and only updated as needed.

In the context of the compiler:

typedef struct {

// Other members redacted

sljit_sw mem_base; // Save the last memory offset of buxn_vm_t

} buxn_jit_ctx_t;

Whenever we need to access memory, call buxn_jit_set_mem_base:

static inline void

buxn_jit_set_mem_base(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, sljit_sw base) {

// If it is different from the current offset

if (ctx->mem_base != base) {

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_ADD,

// Assign to BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE), 0,

// The value of BUXN_JIT_S_VM plus...

SLJIT_S(BUXN_JIT_S_VM), 0,

// The given offset

SLJIT_IMM, base

);

// Save the offset

ctx->mem_base = base;

}

}

It is used like this:

// Point the base to `buxn_vm_t.device`

buxn_jit_set_mem_base(ctx, SLJIT_OFFSETOF(buxn_vm_t, device));

// Point to either the working stack or the return stack

sljit_sw mem_base = flag_r ? SLJIT_OFFSETOF(buxn_vm_t, rs) : SLJIT_OFFSETOF(buxn_vm_t, ws);

buxn_jit_set_mem_base(ctx, mem_base);

Which registers to use for operands?

Take a simple opcode, SUB, which:

- Pops

rhsfrom the stack - Pops

lhsfrom the stack - Calculates

result = lhs - rhs - Pushes

resultinto the stack

What registers can we use for lhs, rhs and result?

How to make sure that it is not something already in use?

“Register allocation” used to sound like a scary term for me but in the context of a stack machine it is much simpler. Recall that operands are temporary, we only have to track which ones are being used within the current VM instruction. To do that, have a bitmap:

typedef struct {

// Other members redacted

uint8_t used_registers;

} buxn_jit_ctx_t;

Every bit tracks the use of one of the “temporary register”: 1 if in use and 0 if free. Set aside a number of scratch registers to be used as operands:

enum {

BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE = 0,

BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET,

// Always available, never allocated but always cloberred between ops

BUXN_JIT_R_TMP,

// Block of operand registers

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_0,

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_1,

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_2,

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_3,

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_4,

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

};

// Track the range of operand registers

enum {

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN = BUXN_JIT_R_OP_0,

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX = BUXN_JIT_R_OP_4,

};

To allocate, scan the bitmap and set the first non-0 bit to 1:

typedef sljit_s32 buxn_jit_reg_t;

static buxn_jit_reg_t

buxn_jit_alloc_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

_Static_assert(

sizeof(ctx->used_registers) * CHAR_BIT >= (BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX - BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + 1),

"buxn_jit_ctx_t::used_registers needs more bits"

);

for (int i = 0; i < (BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX - BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + 1); ++i) {

uint8_t mask = 1 << i;

if ((ctx->used_registers & mask) == 0) {

ctx->used_registers |= mask;

return SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + i);

}

}

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(false, "Out of registers");

return 0;

}

To free set the bit to 0:

static void

buxn_jit_free_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_reg_t reg) {

int reg_no = reg - SLJIT_R0;

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN <= reg_no && reg_no <= BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX, "Invalid register");

uint8_t mask = 1 << (reg_no - BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN);

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT((ctx->used_registers & mask), "Freeing unused register");

ctx->used_registers &= ~mask;

}

Freeing is not always necessary as the bitmap is reset before every instruction:

ctx->used_registers = 0;

Finally, there can be checks when a register is used in “micro ops” such as push:

typedef struct {

// Other members redacted

buxn_jit_reg_t reg; // The register in which this operand is stored

} buxn_jit_operand_t;

static void

buxn_jit_push(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_operand_t operand) {

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(

ctx->used_registers & (1 << (operand.reg - SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN))),

"Pushing operand with unused register"

);

// ...

}

The various asserts helped detecting misuse early.

With all that, the implementation for SUB looks like this:

static void

buxn_jit_SUB(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

// Pop operands from the stack, automatically assigned to a register each

buxn_jit_operand_t rhs = buxn_jit_pop(ctx);

buxn_jit_operand_t lhs = buxn_jit_pop(ctx);

buxn_jit_operand_t result = {

// Other details redacted

// ...

// Allocate a register to store the result

.reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx),

};

// result = lhs - rhs

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_SUB,

result.reg, 0,

lhs.reg, 0,

rhs.reg, 0

);

// Push the result into the stack

buxn_jit_push(ctx, result);

}

Strictly speaking, I did this much later during development. Since operands are temporary, they can be manually assigned as seen in the linked diff. However, it’s one of those things that if I have known earlier, I would do it from the beginning. A bunch of optimizations that I tried later become hard to do since register uses start to overlap. You should not have to suffer the same fate.

Dynamic jump across functions

In any language with first class functions, the target of a function call can be a variable, a value popped from the stack. In uxn, every jump can be dynamic. The target might not even be JIT’ed yet since we only JIT upon entering an un-JIT’ed code block. How to emit code for dynamic jumps? Where would the jump instruction even points at since the target is only known at runtime?

A trampoline 8 can be used:

// A JIT'ed function takes a VM instance and return the next PC (program counter)

typedef sljit_u32 (*buxn_jit_fn_t)(sljit_up vm);

// A JIT'ed code block holds a function pointer

struct buxn_jit_block_s {

// Other members redacted

buxn_jit_fn_t fn; // The JIT'ed function

};

void

buxn_jit_execute(buxn_jit_t* jit, uint16_t pc) {

while (pc != 0) { // Run until termination

// Lookup the cached JIT'ed function.

// This can also trigger a compilation if it is not yet JIT'ed

buxn_jit_block_t* block = buxn_jit(jit, pc);

// Call the JIT'ed function which can return a new PC

pc = (uint16_t)block->fn((uintptr_t)jit->vm);

}

}

To compile a dynamic jump, just return with the new PC:

sljit_emit_return(ctx->compiler, SLJIT_MOV32, SLJIT_IMM, ctx->pc);

Putting everything together

As mentioned earlier, JIT compilation is just a matter of statically tracing the bytecode. The compiler looks much like an interpreter loop:

static void

buxn_jit_compile(buxn_jit_t* jit, uint16_t pc) {

// Create the compilation context

buxn_jit_ctx_t ctx = {

.jit = jit,

.pc = pc,

.compiler = sljit_create_compiler(NULL),

};

// Start the function

sljit_emit_enter(

ctx.compiler,

// Default options

0,

// A function returning the new PC, accepting a pointer to the VM

SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P),

// This many scratch registers

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

// This many saved registers

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

// No local stack variable

0

);

// Statically trace execution until termination

while (!ctx.terminated) {

// Fetch the next instruction

ctx.current_opcode = ctx.jit->vm->memory[ctx.pc++];

// Call the appropriate opcode handler

switch (ctx.current_opcode) {

case ADD: buxn_jit_ADD(&ctx); break;

case SUB: buxn_jit_SUB(&ctx); break;

// ...

}

}

// Wrapping up

buxn_jit_block_t* block = buxn_jit_new_block(jit, pc);

block->fn = (buxn_jit_fn_t)sljit_generate_code(entry->compiler, 0, NULL);

}

Compilation is stopped when a terminating instruction is encountered.

In uxn case, it’s BRK:

static void

buxn_jit_BRK(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

// At runtime, set PC to 0 to signal termination

sljit_emit_return(ctx->compiler, SLJIT_MOV32, SLJIT_IMM, 0);

// At compile time, tell the tracing loop to terminate

ctx->terminated = true;

}

And now, things should be magically faster.

Reality hits

This is barely any faster OTL.

Since every jump can be dynamic, the generated code returns to the trampoline a lot.

Like almost all the time except for some special cases.

With a bunch of indirect jumps to various targets concentrated into a single indirect call: pc = (uint16_t)block->fn((uintptr_t)jit->vm);, this reduces the JIT runtime into a switch dispatch.

In the first place, my interpreter is already pretty optimized with computed goto 9.

This spreads out all the jump sites and help the branch predictor to learn patterns.

For example, after a boolean opcode like EQU, the next opcode is almost always a conditional jump: JCI (Jump Condtional Immediate).

The CPU can speculatively prefetch that code and even execute some instructions while the result is still being calculated.

One of the biggest sources for performance gain is better branch prediction. All the benefits of native compilation is cancelled out just like that.

Pop and push are also naively implemented as memory load and store. For example, this is the code for push:

// Set memory base

buxn_jit_set_mem_base(ctx, mem_base);

// Subtract 1 from the stack pointer register

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_SUB,

stack_ptr_reg, 0,

stack_ptr_reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, 1

);

// Assign the value to the offset register

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U8,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET), 0,

stack_ptr_reg, 0

);

// Load from memory into the operand register

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U8,

reg, 0,

SLJIT_MEM2(SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE), SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET)), 0

);

There are a lot of loads and stores. This is slow because memory is slow. While some of it may be cached, it is not guaranteed. The bytecode interpreter suffers from the same issue but we can do better.

The name of the game is all about: branch prediction and memory access.

Call optimization

This is the first thing to optimize. The modern processors are built to correctly predict a sequence of calls and returns and our JIT’ed code should make use of that. While calls can be dynamic, most of them aren’t and the static calls should be identified. Having done some static analysis for uxn, I know exactly how to do that.

While statically tracing the bytecode, the compiler also keeps a symbolic stack besides just emitting stack manipulation code. Whenever a constant value is pushed into the stack, it is marked as such:

// Bitmasks for the "semantic" of a value

enum {

BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST = 1 << 0, // Is the value a constant?

BUXN_JIT_SEM_BOOLEAN = 1 << 1, // Is the value a boolean?

};

// A value can be identified as a compile time constant with its constant value

// tracked

typedef struct buxn_jit_value_s {

uint8_t semantics;

uint8_t const_value;

} buxn_jit_value_t;

typedef struct {

// Static stack pointer

uint8_t wsp;

// A stack is an array of 256 values

buxn_jit_value_t wst[256];

// Other members redacted

} buxn_jit_ctx_t;

// Pushing a literal to the stack

static void

buxn_jit_LIT(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

buxn_jit_operand_t lit = {

// This is a constant value

.semantics = BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST,

// Allocate register storage

.reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx),

};

// Loading code redacted

// ...

// Push the value to the stack

buxn_jit_push(ctx, lit);

}

Various operations are built on push and pop 10. They propagate const-ness and bool-ness between the stack and the operands:

typedef struct {

// An operand will now also track const-ness

uint8_t semantics;

uint8_t const_value;

// Other members redacted

} buxn_jit_operand_t;

static void

buxn_jit_push(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_operand_t operand) {

// Push a value

buxn_jit_value_t* value = &ctx->wst[ctx->wsp++];

// Propagate const-ness and bool-ness

value->semantics = operand.semantics;

value->const_value = operand.const_value;

// Code generation redacted

// ...

}

static buxn_jit_operand_t

buxn_jit_pop(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

// Create an operand with a register reserved

buxn_jit_operand_t operand = { .reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx) };

// Pop a value

buxn_jit_value_t value = ctx->wst[--ctx->wsp];

// Propagate const-ness and bool-ness

operand.const_value = value.const_value;

operand.semantics = value.semantics;

// Code generation redacted

// ...

return operand;

}

Const-ness and bool-ness can be propagated or eliminated.

For example, in ADD:

static void

buxn_jit_ADD(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

// Retrieve operands

buxn_jit_operand_t rhs = buxn_jit_pop(ctx);

buxn_jit_operand_t lhs = buxn_jit_pop(ctx);

buxn_jit_operand_t result = {

// A value is a constant iff it is added from 2 constants

.semantics = ((lhs.semantics & BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST) && (rhs.semantics & BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST))

? BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST

: 0,

// Resulting constant value, ignored if not a constant

.const_value = lhs.const_value + rhs.const_value,

// Register to hold result

.reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx),

};

// result = lhs + rhs

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_ADD,

result.reg, 0,

lhs.reg, 0,

rhs.reg, 0

);

// Push result into stack

buxn_jit_push(ctx, result);

}

We can see that regardless of any funky stack manipulation, constant values can always be identified. With that, instead of a dynamic jump (return to the trampoline), whenever a jump target is constant, it can be made static:

static void

buxn_jit_jump(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_operand_t target, uint16_t return_addr) {

// If the target is statically known

if (target.semantics & BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST) {

// If this is a call instead of a jump

if (return_addr == 0) {

// Check assumed constant value before jumping

struct sljit_jump* jump = sljit_emit_cmp(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_EQUAL | SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP,

target.reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, target.const_value

);

// Queue the target for JIT compilation

buxn_jit_entry_t* entry = buxn_jit_alloc_entry(ctx->jit);

entry->link_type = BUXN_JIT_LINK_TO_BODY;

entry->block = buxn_jit_queue_block(ctx->jit, target.const_value);

entry->compiler = ctx->compiler;

entry->jump = jump;

buxn_jit_enqueue(&ctx->jit->link_queue, entry);

} else {

// Check assumed constant value before calling

struct sljit_jump* skip_call = sljit_emit_cmp(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_NOT_EQUAL,

target.reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, target.const_value

);

// Make a function call

struct sljit_jump* call = sljit_emit_call(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_CALL | SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP,

SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P)

);

// Skip the call if assumption is wrong

sljit_set_label(skip_call, sljit_emit_label(ctx->compiler));

// Queue the target for JIT compilation

buxn_jit_entry_t* entry = buxn_jit_alloc_entry(ctx->jit);

entry->link_type = BUXN_JIT_LINK_TO_HEAD;

entry->block = buxn_jit_queue_block(ctx->jit, target.const_value);

entry->compiler = ctx->compiler;

entry->jump = call;

buxn_jit_enqueue(&ctx->jit->link_queue, entry);

}

}

// Return to trampoline.

// This is always correct but slow.

sljit_emit_return(ctx->compiler, SLJIT_MOV32, target.reg, 0);

}

Several things need to be explained:

- Why must the constant value be checked at runtime?

- What is

SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP? - What is queueing and

BUXN_JIT_LINK_TO_HEADvsBUXN_JIT_LINK_TO_BODY?

Checking assumption against loops and self-modifying code (SMC)

First, the simple static analyzer is naive and assume the best case. Considering a loop: The loop counter can start as a constant, only ever added with a constant and yet, the result is variable. What is considered constant by this static stack might not be so.

Second, this is a problem unique to uxn: self-modifying code (SMC). In the general case, that would destroy any form of JIT compilation. However, in practice, it is only ever used for modifying literal values called doors. This is very similar to static variables in C. The static type checker, working at both the bytecode and source level can correctly identify such code patterns. However, at the bytecode level, the JIT runtime cannot do that. Thus, it will make optimistic assumptions, recheck it at runtime and fallback to a safe but slow code path.

In the best case, these conditional branches are never taken and the branch predictor would be able to predict with 100% accuracy. Even in a loop, the returning jump back to the loop beginning is taken in all iterations but one. Branch predictors are usually built for that. Those checks and conditional jumps should be cheap. In the worst case, dynamic jumps are already slow to begin with even in native code. We already have nothing to lose if the target keeps changing. For example: calling a virtual method in an array of objects of various types.

Linking code blocks with SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP

One code block can jump or call into another. The target might not be JIT’ed yet. Moreover, we can have self recursion (a function calling into itself) or mutual recursion (two functions calling each other).

In other words, there is no obvious order in which code blocks should be JIT’ed. The solution is:

- While compiling a code block, just take note of jump targets and enqueue them for compilation.

- Emit all jumps to a temporary target (trampoline).

Mark all jumps with

SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP. - After finishing with the current code block, compile other blocks in the queue if needed. A code block can be the target of multiple jumps but it is only compiled once.

- Rewrite all jumps with

sljit_set_targetto point to the non-trampoline jump site.

This is a very powerful feature in SLJIT which can be used for a tracing JIT: to retarget jumps when recompilation happens. In our case, it just makes resolving recursion simpler. Much like a C compiler, we assume that jump targets are defined “somewhere” following a forward declaration. Then in a separate link phase, the jumps are wired to their targets like how a linker … links compiled object files 11.

Linking to head vs body

In uxn, a jump can be a normal jump (JMP) or a stash jump (JSR).

In the latter case, the return address is pushed into a return stack, much like a function call.

Even in other languages, there’s also the concept of tail-call where execution continues into another function without returning to the caller.

This means a direct jump target (e.g: function) can be used for both calls (with return) and direct jump (no return).

We do not want to compile two separate copies of every function just for that.

Recall that a function begins with: sljit_emit_enter.

Internally it sets up a function prologue for the native calling convention.

A tail call or a direct jump just means skipping that prologue.

At the start of a function, emit 2 separate labels:

// A SLJIT_CALL lands here, before the prologue

ctx.head_label = sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler);

sljit_emit_enter(

ctx.compiler,

0,

SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P),

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

0

);

// A SLJIT_JUMP lands here, skipping the prologue

ctx.body_label = sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler);

The next time the code generated by sljit_emit_return is executed, it would return to the caller in the case of SLJIT_CALL/head and the previous caller in the case of SLJIT_JUMP/body.

In the latter case, no return address was pushed and since JIT’ed functions all share the same signature, the original prologue matches the tail-called epilogue, making it safe to jump between different functions.

We now have a single function implementation being compatible with both normal calls and tail calls.

Simply check the link_type field to determine the jump target:

// Compile queue processing happens first

// ...

// Resolve link queue

while ((entry = buxn_jit_dequeue(&jit->link_queue)) != NULL) {

// Target can be either head or body

sljit_uw target = entry->link_type == BUXN_JIT_LINK_TO_HEAD

? entry->block->head_addr

: entry->block->body_addr;

// Link a jump to its label

sljit_set_jump_addr(

sljit_get_jump_addr(entry->jump),

target,

entry->block->executable_offset

);

}

The result

This optimization alone is responsible for the majority of the performance gain.

But optimization works continue.

Lightweight calling convention

One would immediately see SLJIT_ENTER_REG_ARG when looking at SLJIT’s documentation.

It is introduced as a lightweight calling convention, not compatible with C.

Most of the time, we are jumping between uxn code blocks so C compatibility is not a concern.

Moreover, calling between JIT’ed functions also have a memory access cost not mentioned until now.

A VM instance pointer (buxn_vm_t*) is the only argument passed between functions.

However, there are also two stack pointers: wsp and rsp.

Upon entering and exiting they have to be save into and loaded from the VM instance.

Those are unnecessary memory accesses which could slow down the program.

SLJIT_ENTER_REG_ARG is a calling convention where a number of “saved” registers are not saved/restored between functions.

Instead, they are kept intact as “context”.

This is perfect for our usecase: keeping the pointer to the VM and the two stack pointers in registers between uxn functions.

The only problem left is to resolve C compatibility at entrance from buxn_jit_execute.

Moreover, trampoline and indirect jumps are still possible in the general case, necessitating C compatibility.

As usual, compiling separate copies is not an attractive idea.

But all problems can be resolved with a level of indirection.

Just compile every code block with an outer C-compatible wrapper and an inner fast calling body:

static void

buxn_jit_compile(buxn_jit_t* jit, uint16_t pc) {

// C-compatible prologue

sljit_emit_enter(

ctx.compiler,

0,

SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P),

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

0

);

// Load stack pointers from vm

buxn_jit_load_state(&ctx);

// Call into the C-incompatible body

struct sljit_jump* call = sljit_emit_call(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_CALL_REG_ARG,

// Takes no argument and returns the next PC

SLJIT_ARGS0(32)

);

// Upon return, save stack pointers to vm

buxn_jit_save_state(&ctx);

// Return to the caller

sljit_emit_return(ctx.compiler, SLJIT_MOV32, SLJIT_R0, 0);

// The head for internal calls

ctx.head_label = sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler);

// Link the outer wrapper call here

sljit_set_label(call, ctx.head_label);

// sljit-specific fast calling prologue

sljit_emit_enter(

ctx.compiler,

// Keep all the saved registers between functions and don't save/restore

SLJIT_ENTER_KEEP(BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT) | SLJIT_ENTER_REG_ARG,

SLJIT_ARGS0(32),

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

0

);

// The body for internal jumps

ctx.body_label = sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler);

// Code generation

// ...

}

Internal calls (e.g: JSR) are now compiled like this:

static void

buxn_jit_jump(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_operand_t target, uint16_t return_addr) {

// ...

struct sljit_jump* call = sljit_emit_call(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_CALL_REG_ARG | SLJIT_REWRITABLE_JUMP, // Used to be SLJIT_CALL

SLJIT_ARGS0(32) // Used to be SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P)

);

// ...

}

This is by far the optimization with the higest gain to effort ratio: Just by switching internal calling convention and writing a wrapper, we eliminated a lot of register saving/spilling and memory accesses.

Stack access elimination

As stated before, memory access should be eliminated as much as possible. Ideally, temporaries should never be spilled into the stack and kept in registers. This is at odd with a stack machine regardless of whether the source language is stack-based or not. It loves to push and pop.

Intuitively, we can keep a “cache” of operands. Whenever a push is supposed to happen, don’t immediately generate the native code for that. Instead, push the operand into a “stack cache”. Whenever a pop is supposed to happen, pop from the cache first.

In a stack machine, there are many situations where something is pushed and then immediately popped . For example:

- Comparing two values, pushing the boolean result.

- Popping the result as condition for a jump.

With this stack cache, the intermediate push/pop can be eliminated.

Moreover, even the operands for the original comparison could be temporaries.

The stack cache could also eliminate that.

The generated code would just do operations on registers, shuffling them around in a compile-time stack.

Only the “micro ops”, buxn_jit_push and buxn_jit_pop, which are used to build every other opcodes have to be rewritten.

The rest (e.g: ADD, JMP…) should “just work”.

Here comes the edge cases:

- We do not have 256 registers (double that for the return stack). Strictly speaking, in x86-64, a couple of vector registers could hold the entire stack space of uxn. But that is not always available in all platforms. So when the stack cache is full, some values at the bottom have to be spilled to memory.

- External calls to C means we have to spill registers to memory again.

- Even with internal calls, each functions are compiled separately with registers shuffled in different order in their own stack cache. Function signature is an addon at source level, only enforced by the type checker. This info not saved anywhere in the bytecode. In other words, for internal calls and jumps, we have to spill again.

- Finally, upon entry, the stack cache is empty so a pop has to reach into memory.

After all, this is a cache and even with its limitations, much of the internal temporary values never hit memory. We have not only eliminated a lot of memory access but the generated code is also smaller, potentially fit into the instruction cache better in the case of loops.

Register allocation revisited

The previous register allocation scheme is no longer suitable. A register can stay in-use between instructions. Instead of a bitmap, switch to reference counting:

typedef struct {

// Other fields redacted

// ...

// Reference count for each operand register

uint8_t reg_ref_counts[BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX - BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + 1];

} buxn_jit_ctx_t;

// Bump ref count up

static void

buxn_jit_retain_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_reg_t reg) {

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN <= reg - SLJIT_R0 && reg - SLJIT_R0 <= BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX,

"Invalid register"

);

ctx->reg_ref_counts[reg - SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN)] += 1;

}

// Drop ref count

static void

buxn_jit_release_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_reg_t reg) {

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(

BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN <= reg && reg <= BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX,

"Invalid register"

);

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(

ctx->reg_ref_counts[reg - SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN)] > 0,

"Releasing unused register"

);

ctx->reg_ref_counts[reg - SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN)] -= 1;

}

Now buxn_jit_alloc_reg is a bit more complex:

// Helper to find a free register

static buxn_jit_reg_t

buxn_jit_find_free_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

for (int i = 0; i < (BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MAX - BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + 1); ++i) {

// Find a register with ref count of 0

if (ctx->reg_ref_counts[i] == 0) {

return SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_OP_MIN + i);

}

}

// Found nothing

return 0;

}

// The actual allocation function

static buxn_jit_reg_t

buxn_jit_alloc_reg(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx) {

buxn_jit_reg_t reg;

// Keep trying in a loop

while (

// If we find no free register

(reg = buxn_jit_find_free_reg(ctx)) == 0

&&

// And there is something in the cache(s)

ctx->wst_cache.len > 0

) {

// Try to spill the cache

buxn_jit_stack_cache_spill(ctx, &ctx->wst_cache);

}

BUXN_JIT_ASSERT(reg != 0, "Out of registers"); // Something has gone terribly wrong

// Bump the ref count as it is 0 now

buxn_jit_retain_reg(ctx, reg);

return reg;

}

An operand can be pushed multiple times into the stack (e.g: due to DUP).

Merely spilling out a register (from the bottom of the stack) does not mean it is not in use somewhere else in the middle of the stack.

Reassigning a register immediately after spilling is not safe, hence the spilling loop and reference counting.

A lot of opcodes just allocate registers before pushing (e.g: ADD as seen above) so spilling also happens upon register allocation and not just pushing into a full stack cache.

The book keeping between instructions has to be updated:

// Set all reference counts to 0

memset(ctx->reg_ref_counts, 0, sizeof(ctx->reg_ref_counts));

// Bump ref count for each occurence of a register

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < ctx->wst_cache->len; ++i) {

buxn_jit_retain_reg(ctx, ctx->wst_cache->cells[i]->reg);

}

With this, register allocation seamlessly works with stack caching.

Short mode woes

If you are not targetting a VM like uxn, skip ahead. In uxn, “short mode” refers to an opcode flag where 2 bytes are used instead of 1. The operands can be either 8 or 16 bit depending on this flag. This makes popping a lot more branchy:

static buxn_jit_reg_t

buxn_jit_stack_cache_pop(

buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx,

buxn_jit_stack_cache_t* cache,

bool flag_2

) {

// Is this return mode?

bool flag_r = cache == &ctx->rst_cache;

if (flag_2) { // In short mode

if (cache->len == 0) {

// There is nothing in the cache, pop from memory

// `buxn_jit_pop_from_mem` is the same naive stack access codegen

// function we had before the stack cache.

return buxn_jit_pop_from_mem(ctx, flag_2, flag_r);

} else {

// There is something in the cache

buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t* top = &cache->cells[--cache->len];

if (top->value.is_short) {

// The top value is the right size, just return it

return top->value.reg;

} else {

// The top value is a byte, pop the high byte from the stack

buxn_jit_reg_t hi = buxn_jit_stack_cache_pop(ctx, cache, false); // Call this same function again

// Shift the high byte up

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_SHL,

hi, 0,

hi, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, 8

);

// Combine it with the low byte

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_OR,

hi, 0,

hi, 0,

top->value.reg, 0

);

// Release the low byte register

buxn_jit_release_reg(ctx, top->value.reg);

return hi;

}

}

} else { // In byte mode

if (cache->len == 0) {

// There is nothing in the cache, pop from memory

return buxn_jit_pop_from_mem(ctx, flag_2, flag_r);

} else {

buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t* top = &cache->cells[cache->len - 1];

if (top->value.is_short) {

// The top value is a short, try to split it

// Alloc a register to hold the low byte

buxn_jit_reg_t reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx);

// Allocating a register could force a spill

if (cache->len == 0) {

// Try to pop from memory instead

buxn_jit_release_reg(ctx, reg); // We don't need this anymore

return buxn_jit_pop_from_mem(ctx, flag_2, flag_r);

} else {

// Actually try to split the top value

// Retrieve the low bytes

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U8,

reg, 0,

top->value.reg, 0

);

// Shift the high byte down

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_LSHR, // Logical shift right

top->value.reg, 0,

top->value.reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, 8

);

// The top value is now a byte, not a short

top->value.is_short = false;

return reg;

}

} else {

// The top value is the right size, just return it

cache->len -= 1;

return top->value.reg;

}

}

}

}

Yes, that is the actual code. There is nothing advanced about it but the combination of the two modes and the possibility of cache miss and spill creates a lot of branches (in the compiler, not the generated code).

Keep mode woes

If you are not targetting a VM like uxn, skip ahead again.

In uxn, all opcodes can have a keep mode enabled.

This means it will not actually pop values from the stack but only reference them.

Consider this code: #01 #02 ADDk.

The result will leave 01 02 03 on the stack since 01 and 02 are not actually popped.

Normally, this is implemented using a separate “shadow” stack pointer. In keep mode, popping decrement this pointer, leaving the actual stack pointer intact. But pushing still moves this pointer forward. Things get a lot more complex with a stack cache:

- Does it have its own shadow stack pointer?

- What happens if only the shadow pointer reaches 0 and start reaching into memory?

- What happens when only a few items are shadow popped and then a new item is pushed?

In the end, I settled for a simple solution. First, track the “flush” state and the “cached” state separately:

// A stack cache is a collection of cells

typedef struct {

// Each cell holds an operand

buxn_jit_operand_t value;

// And a flag indicating whether it needs to be flushed into memory

bool need_flush;

} buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t;

typedef struct {

// The cells

buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t cells[BUXN_JIT_CACHE_SIZE];

// The size of the stack

uint8_t len;

} buxn_jit_stack_cache_t;

The new cache policy is as follow:

- Whenever keep mode is on, flush the entire cache into memory, setting the value of

buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t.need_flushtofalse. However, keep the cached content. - Regardless of modes, popping always pop from the stack cache. This avoids an unnecessary load back from memory even if the cache is already flushed. Due to intervening operations, we cannot bet on the value to stay resident in the CPU cache.

-

Regardless of modes, pushing allways push to the stack cache, setting

buxn_jit_stack_cache_cell_t.need_flushtotrueon the new cell. Even if a spill due to a full stack happens, a cell is never flushed twice thanks to this flag. This is safe to do since all opcodes are implemented in this pattern:- Pop operands from the stack

- Perform calculation

- Push results to the stack

At this point the stack cache is in a different shape from what it is supposed to represent. For example:

#01 #02 INCkis supposed to leave01 02 03in the stack. However, the stack cache has:01 03since popping in keep mode will actually pop from it. The in-memory stack has:01 02since03is not yet flushed. - In between opcodes, discard (not flush) all items with

need_flush == falsein the stack cache. This brings the stack cache back in sync. Going back to the above example, since01and02are already flushed,01will be discarded from a cache of01 03, leaving03. With the memory stack having01 02, the stack cache is now correct since together, they form:01 02 03.

This policy keeps the stack cache correct while still retaining some memory access elimination property. It is only temporarily incorrect during pushing which always happen at the end of an opcode and it will be immediately corrected before the next opcode. Take note that all of this happens in (JIT) compile-time, not runtime.

The result

This is another optimization that has great effects. It requires a lot more effort than the call optimization. However, the JIT’ed code can now takes advantage of a register machine a bit better.

Other optimizations

There are other smaller optimizations that does not fit in any categories. They are relatively simple compared to the 2 major ones above.

Combining immediate loads

In uxn, several opcodes like LIT2, JCI and JMI load a short from the ROM at an address directly following the opcode (called an immediate value).

In a sense, they take an operand and uxn is not a machine with purely nullary opcodes 12.

A naive implementation of immediate short load looks like this:

static buxn_jit_operand_t

buxn_jit_immediate(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_reg_t reg, bool is_short) {

buxn_jit_operand_t imm = {

// Assume that it is a constant, even if it can be overwritten.

// Jump opcodes will recheck the assumption so it is safe.

.semantics = BUXN_JIT_SEM_CONST,

.is_short = is_short,

.reg = buxn_jit_alloc_reg(ctx),

};

// Set the base memory register to vm->memory

buxn_jit_set_mem_base(ctx, SLJIT_OFFSETOF(buxn_vm_t, memory));

if (is_short) {

// Set the offset register to the program counter (PC)

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx>compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U16,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET), 0,

SLJIT_IMM, ctx->pc

);

// Load the high byte

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx>compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U8,

imm.reg, 0,

SLJIT_MEM2(SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE), SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET)), 0

);

// Shift it up

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx>compiler,

SLJIT_SHL,

imm.reg, 0,

imm.reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, 8

);

// Set the offset register to the low byte at PC+1

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U16,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET), 0,

SLJIT_IMM, ctx->pc + 1

);

// Load the low byte to a temporary register

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U8,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_TMP), 0,

SLJIT_MEM2(SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE), SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET)), 0

);

// Combine it with the high byte

sljit_emit_op2(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_OR,

imm.reg, 0,

imm.reg, 0,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_TMP), 0,

);

// Bump the PC

ctx->pc += 2;

} else {

// Byte load code redacted

// ...

}

return imm;

}

That’s two separate back-to-back loads. They can be combined:

static buxn_jit_operand_t

buxn_jit_immediate(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_reg_t reg, bool is_short) {

// Same prelude as before

// ...

if (is_short) {

if (ctx->pc < 0xffff) { // No wrap around, do combined load

// Set memory offset to PC

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U16,

SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET), 0,

SLJIT_IMM, ctx->pc

);

// Perform an unaligned load

sljit_emit_mem(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_U16 | SLJIT_MEM_LOAD | SLJIT_MEM_UNALIGNED,

imm.reg,

SLJIT_MEM2(SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_BASE), SLJIT_R(BUXN_JIT_R_MEM_OFFSET)), 0

);

// Flip byte order in little endian architectures

#if SLJIT_LITTLE_ENDIAN

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_REV_U16,

imm.reg, 0,

imm.reg, 0

);

#endif

} else { // Separate loads as before

// ...

}

} else { // Byte load

// ...

}

return imm;

}

Even with the potentially unaligned load penalty and the extra endian swap, this does make a difference.

Boolean jump

This is a pattern commonly found in uxn: %max ( a b -- max ) { GTHk JMP SWP POP }.

It reads:

- Check whether

a > b, keeping both in the stack but push a boolean value (0 or 1) into the stack. The stack now contains 3 items:a b a>b? -

Pop a byte value from the stack and jump a signed distance equal to it.

- If

a>b? == 1, theSWPopcode is skipped since a jump of distance 1 happenned. - If

a>b? == 0, theSWPopcode is executed next since a jump of distance 0 happened.

- If

- (Conditionally) swap the top two values in the stack. Whether this happens depends on the previous step.

- Pop the top value from the stack. This will always be the smaller values due to the above conditional swap.

Since step 2 is a jump using a variable, it will return to the trampoline. Given that this pattern of “boolean jump” is common, it should be optimized. That is the reason “bool-ness” is tracked in the static stack during tracing. Whenever a jump takes a boolean as input, it is converted into a conditional jump:

static void

buxn_jit_jump(buxn_jit_ctx_t* ctx, buxn_jit_operand_t target, uint16_t return_addr) {

// ...

if (target.semantics & BUXN_JIT_SEM_BOOLEAN) {

// Conditional jump to skip the next opcode

struct sljit_jump* skip_next_opcode = sljit_emit_cmp(

ctx->compiler,

SLJIT_NOT_EQUAL,

target.reg, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, 0

);

// Generate code for the next opcode

buxn_jit_next_opcode(ctx);

// The opcode might be a terminating one (like BRK or indirect jump)

// but we ignore that and move along since it may not even execute

ctx->terminated = false;

// In case the previous opcode was executed, clear the stack cache

// so that the next opcode starts in a consistent state for both

// true and false branches

buxn_jit_clear_stack_caches(ctx);

// Jump here to skip

sljit_set_label(skip_next_opcode, sljit_emit_label(ctx->compiler));

}

// ...

}

Since the two branches are now joined, the stack cache is in an indeterminate state and it has to be cleared. This saves a return to trampoline at the cost of more memory load/store.

Simplify POP

The opcode POP is simply implemented as the micro op buxn_jit_pop.

However, this creates an unnecessary memory load when the value is just discarded.

POP is implemented again without using buxn_jit_pop.

The “branchy-ness” is not as bad since we don’t care about the stack content.

This optimization has significant effects in certain benchmarks. It is probably due to the nature of a stack language where POP is used for balancing the stack a lot. In languages with a local stack frame, it is already a cheap operation: subtracting from the stack pointer at runtime, discarding the stack frame at compile time. The concept of a “stack frame” does not even exist in a stack language. We also have a stack cache to maintain.

JIT the trampoline

The trampoline can be inlined at the start of every JIT’ed function:

static void

buxn_jit_compile(buxn_jit_t* jit, const buxn_jit_entry_t* entry) {

// ...

// C-compatible prologue

sljit_emit_enter(

ctx.compiler,

0,

SLJIT_ARGS1(32, P),

BUXN_JIT_R_COUNT,

BUXN_JIT_S_COUNT,

0

);

buxn_jit_load_state(&ctx);

// Call into the fast body

struct sljit_jump* call = sljit_emit_call(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_CALL_REG_ARG,

SLJIT_ARGS0(32)

);

// Trampoline for indirect jumps

struct sljit_label* lbl_trampoline = sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler);

// Jump out of the loop if the body returns 0 as the next address

struct sljit_jump* jmp_brk = sljit_emit_cmp(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_EQUAL,

SLJIT_R0, 0, // The return value is in R0

SLJIT_IMM, 0

);

// Otherwise, put the address as the second argument in R1

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_MOV32,

SLJIT_R1, 0,

SLJIT_R0, 0

);

// Put the jit as the first argument in R0

sljit_emit_op1(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_MOV_P,

SLJIT_R0, 0,

SLJIT_IMM, (sljit_sw)jit

);

// Call a helper function to locate the next target

sljit_emit_icall(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_CALL,

SLJIT_ARGS2(W, P, 32),

SLJIT_IMM, SLJIT_FUNC_ADDR(buxn_jit_translate_jump_addr)

);

// Call the target using the internal calling convention

sljit_emit_icall(

ctx.compiler,

SLJIT_CALL_REG_ARG,

SLJIT_ARGS0(32),

SLJIT_R0, 0

);

// Jump back to the start of the loop

sljit_set_label(sljit_emit_jump(ctx.compiler, SLJIT_JUMP), lbl_trampoline);

// Break out of the trampoline here

sljit_set_label(jmp_brk, sljit_emit_label(ctx.compiler));

// Return to caller

buxn_jit_save_state(&ctx);

sljit_emit_return(ctx.compiler, SLJIT_MOV32, SLJIT_R0, 0);

// sljit-specific fast calling convention

// ...

}

// Helper for address translation and JIT'ing the target

static sljit_uw

buxn_jit_translate_jump_addr(sljit_up jit, sljit_u32 target) {

buxn_jit_block_t* block = buxn_jit((buxn_jit_t*)jit, target);

return block->head_addr;

}

With that buxn_jit_execute is now simply:

void

buxn_jit_execute(buxn_jit_t* jit, uint16_t pc) {

buxn_jit_block_t* block = buxn_jit(jit, pc);

block->fn((uintptr_t)jit->vm);

}

The hypothesis is that even with indirect jumps, sometimes the target is not so frequently changed. With multiple trampolines, the branch predictor can learn the history of each separate function instead of them all being combined into one. However, I have not found a benchmark where this matters.

Debugging techniques

There are a couple of techniques I found quite useful while debugging.

IR decorator

SLJIT allows dumping the IR with sljit_compiler_verbose.

However, it is a lot of code and it is hard to find out which SLJIT IR chunk corresponds to which uxn bytecode chunk (or even micro ops).

What I found useful is to also emit debug log into the same stream, as comments:

; 0x0100 {{{

; Prologue {{{

enter ret[32], args[p], scratches:9, saveds:3, fscratches:0, fsaveds:0, vscratches:0, vsaveds:0, local_size:0

mov.u8 s1, [s0 + 32]

mov.u8 s2, [s0 + 33]

call_reg_arg ret[32]

mov.u8 [s0 + 32], s1

mov.u8 [s0 + 33], s2

return32 r0

label:

; }}}

enter ret[32], opt:reg_arg(3), scratches:9, saveds:3, fscratches:0, fsaveds:0, vscratches:0, vsaveds:0, local_size:0

label:

; LIT2 {{{

; alloc_reg() => r3

; retain_reg(r3) => 1

; r3 = rom(addr=0x0101, flag_2=1)

add r0, s0, #802

mov.u16 r1, #257

load.u16.unal r3, [r0 + r1]

rev.u16 r3, r3

; push(reg=r3, flag_2=1, flag_r=0)

; retain_reg(r3) => 2

; }}}

; retain_reg(r3) => 1

; WST: r3*

; Shadow stack {{{

; alloc_reg() => r4

; retain_reg(r4) => 1

; alloc_reg() => r5

; retain_reg(r5) => 1

mov.u8 r4, s1

mov.u8 r5, s2

They can be highlighted in text editors as assembly.

The {{{ and }}} are fold markers.

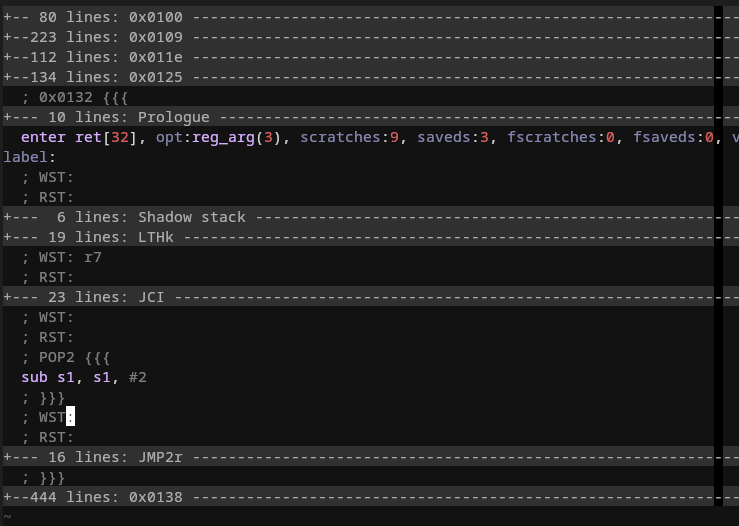

I can collapse an entire code block or portions of it to keep them from view and only “zoom in” the interesting parts:

In the above image, only the IR for POP2 is expanded while all other code blocks and opcodes are collapsed.

The retained registers in the stack cache is also printed in between opcodes.

This helps a lot in locating compiler errors.

GDB integration

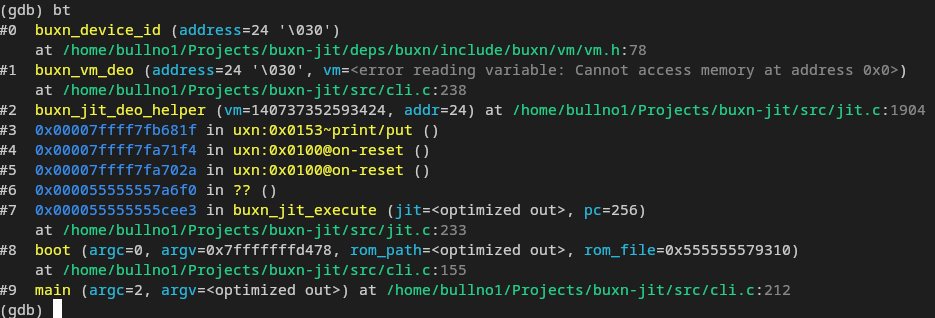

It turned out that GDB has support for debugging JIT’ed code. The debug info can be in any arbitrary format since there is support for creating a reader plugin. It can be as detailed or coarse-grained as you want. In my case, it is enough to show the PC and the nearest label:

In the above image, a backtrace can be seen starting from C code, going into JIT’ed uxn code and back out into C code again. Stepping through uxn code takes a bit of effort so it was not done yet. Besides, I already have a debugger for interpreter mode 13. This is more for debugging the JIT compiler and the interaction with native code (e.g: Are the correct blocks JIT’ed, do they call into native code with the correct arguments…).

A couple of notes:

- The

__jit_debug_register_codefunction must be declared like this. It prevents the optimizer from removing it in release mode. Everything from the empty inline asm block and attributes are required. - When built as a static library,

__jit_debug_descriptormust be forced exported. Otherwise, gdb will mysteriously asserts and crashes. - Put

set debug jit onin gdb so it prints something about the JIT reader plugin.

These should save you several hours of headache.

Conclusion

From SLJIT’s overview:

Just like any other technique in a programmer’s toolbox, just-in-time (JIT) compilation should not be blindly used. It is not a magic wand that performs miracles without drawbacks.

The initial naive application didn’t even yield much gains. Only after a bunch of optimizations that it really shines: a 30-46% speedup compared to the computed goto interpreter. On a CM5, CPU usage when running uxn-beat is reduced from 60% (interpreter) to around 40% (JIT). And even that doesn’t even sound magical enough 14.

A stack machine is an attractive target for compiler writers, esp new comers but making it fast is not trivial. I hope you have learnt a few ways to achieve that. Now go out there and JIT.

-

The expression parser is zserge/expr. Only much later, I found out that it was created specifically to power Glitch, a bytebeat inpsired program. ↩

-

Like some ESP32 such as Cardputer. ↩

-

Technically the one source file can conditionally include other source files depending on the platform. But that is hidden from the user. Regardless of build systems, it’s still one single source file. ↩

-

There are probably other processors that work like that but x86 is what I am most familiar with, childhood and all. ↩

-

This is a really nice API. In my previous compilers, what I’d do is:

- Have an “allocate a label” function

- A jump emitting function requires a label as an input

- Create a separate “place the label here” function so a jump target can still be defined after a jump instruction

Compared to sljit, it still has the problem of creating a “jump to nowhere” if the label placement function is not called. Moreover, in code fragments where multiple jumps have the same target, it is not so obvious when reading the code since they all have different labels. ↩

-

The book titled “folk C programming techniques” passed down for generations. It mentions things like this and arena allocator. ↩

-

From Wikipedia:

As used in some Lisp implementations, a trampoline is a loop that iteratively invokes thunk-returning functions.

That’s a lot of mumbo-jumbo but it will be demonstrated later in this post. ↩

-

Many moons ago, I also wrote about a portable technique when computed goto is not available: https://bullno1.com/blog/switched-goto. ↩

-

If you are familiar with uxn, just assume working stack and byte mode in all the samples. This is needed to simplify the sample code a bit. A user-accessible return stack is not common in other languages. ↩

-

There is link time optimization but this is a simplified view of a linker. ↩

-

laki is an uxn-inspired design that takes it further. It gives immediate mode to (almost) all opcodes. ↩

-

Having the bytecode interpreter and the JIT runtime being different functions allows for disabling JIT when a debugger is attached. ↩

-

LuaJIT is really some arcane black magic. ↩