Building a build tool

Build tools, every “compiled” language has one of these. Some have several. They are usually pretty good at building their own language and absolutely horrible at everything else. I still can’t for the life of me figure out how to set proper g++ flags in gradle for example. Many of my projects use several languages at the same time, have to be built on multiple platforms and with different configurations so it’s always a PITA 1. If only there were a tool to tie all those build tools together [^2].

The problems with make

For quite a while, that tool was GNU make. For simple tasks, it works fine. However, I often need to write rules similar to this:

This file depends on a list of files with names matching this pattern in this folder. If any file changes or the list of file changes (added/removed), rebuild the file using this command.

I still don’t know how to write this in Makefile, often I have to opt to rebuild that everytime. And then there are things that need automation and dependency tracking but are not programming languages like audio, textures… Moreover, Makefile also has other problems. A better general purpose build tool is needed.

Designing my own tool is quite time consuming so after Googling around, I found djb’s redo. He never released the actual tool and only a series of posts under the deceivingly simple title: “Rebuilding target files when source files have changed” outlining its design. The pros and cons of redo can be found all over the web but here’s a summary of why I chose it:

- No new language/syntax to learn: a redo build script (.do file) is just a shell script.

You get editor highlighting for free.

Chances are you already have some adhoc shell scripts lying around.

With redo, you can easily adjust them to have dependency tracking built-in (e.g:

script 1only runscript 2iftarget Awas updated).redois just a collection of programs that can be called from any scripts. You can even write your build scripts in Ruby or Python. - Changes are tracked using checksums instead of timestamp: NFS shares, virtual machines (vagrant) mess this up all the time.

- Atomic output: have you ever cancelled a build half-way with Ctrl+C, resumed it later only to find out that it’s corrupted “somewhere”.

It’s time for

sword fightinga full rebuild. - And the most important point: build output depends on build settings.

make clean && make targetgets old really fast. With redo, once you change a build script, the target is automatically considered outdated.

Redoing redo

As usual, before my NIH syndrome kicks in, I googled around for existing implementations.

It seems everyone implemented it using their own favourite language just because.

apenwarr’s implementation looks like the most complete and well-documented.

I almost use that if not for a not so small problem: how to deploy it?

It’s a bunch of scripts that must be in the execution path.

git submodule and then add to PATH?

Write my own package for literally millions of distros?

Write a long winded instruction of how to setup the build environment for people who clone my project?

I decided to write my own implementation in shell script around the time I had a project that works with busybox.

That was when it clicks: I will write my redo in busybox-style.

This means only a single script for all of redo commands (redo-ifchange, redo-ifcreate…).

Depending on the basename the script is called under, it acts differently.

That’s it no more packaging or distribution woes.

Only a single script dropped in and all my polyglot/multiplatforms problems will be gone [^3].

After using and refining it through 3 projects [^4], I am quite pleased. Like most things designed by djb, it’s well thought out.

What went right

Single script build tool ftw!

Just copy and paste it in a project and I’m ready to start. My client didn’t have a problem reproducing the build after I handed my code to them.

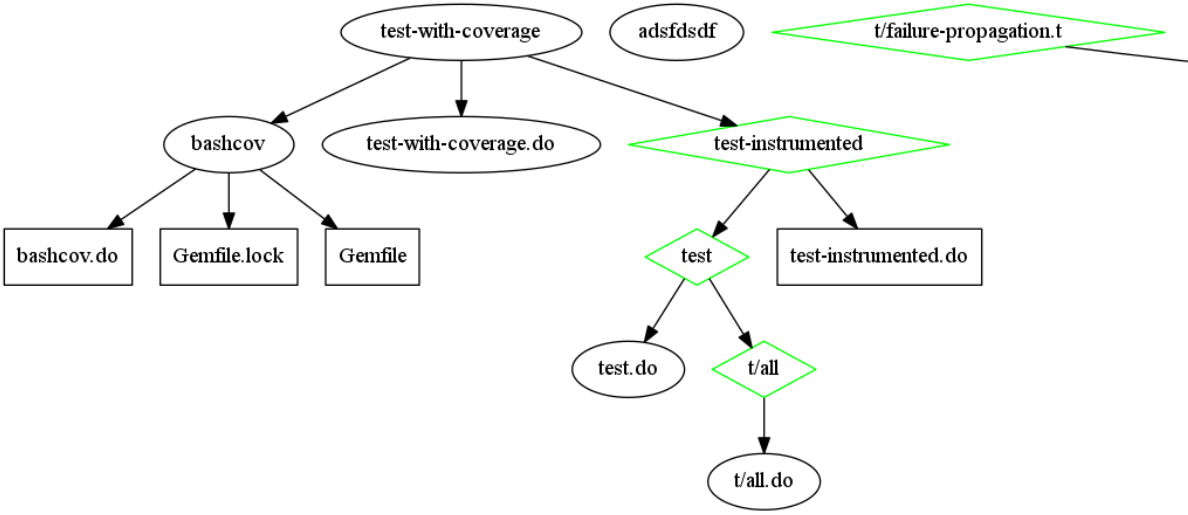

Dependency graph generation

In the picture above, target test-with-coverage will use ruby-bundler to install bashcov, a shell script coverage tool before running tests.

Whenever Gemfile or Gemfile.lock changes (i.e: when I decided to use a different version of bashcov), it will be rebuilt.

Currently, this feature is only useful for debugging redo itself but I may need it to debug more complicated rules.

Automatically inferred clean rule

By design, redo keep tracks of all sources and targets in a central database.

This means “clean” rules can be automatically inferred.

redo --clean will automatically deletes all targets [^5].

Copypasta-able log ftw!

Technically, this feature is copied from apenwarr’s implementation.

However, I added my some of my own refinement.

Often when a build with make fails, the user is left clueless.

Turn on verbose logging and it’s too much output.

Most of the time one only has to rerun a few commands, see what’s wrong and modify the build scripts.

My redo outputs logs as follow:

redo test

redo t/all

: Running testcase ./use-relative-path

redo t/use-relative-path.t

redo test

redo all

redo rel/rel_target

redo rel/rel_target2

redo rel_target

redo all

: Running testcase ./cd-to-script-dir

redo t/cd-to-script-dir.t

redo test

: Running testcase ./params

redo t/params.t

redo test

redo a

redo b

redo no-inherit

redo child

redo all

: Running testcase ./logwrap

redo t/logwrap.t

redo test

redo all

: aasdfasdf

The output is valid shell script and can be copy-pasted into the terminal for debugging.

Log messages are prepended with : (the empty command) so it’s safe for pasting.

There are several log levels and only the most verbose will be printed by default.

Messages are indented everytime a target depends on another one.

This helped tremendously when writing build scripts.

What went wrong

Shell script was not a good choice

I don’t know how the plowshare developers did it but frankly I couldn’t write something moderately complex with shell script.

At first, I tried my best to keep redo it POSIX-compliant.

Soon, I discovered that local variable is a non-standard extension.

Fortunately, almost every shell supports it.

Functions in shell scripts can’t return a string value. I got “creative” and decided to make them assign result to a global variable. Caller must immediately assign that to its local variable and continue. Surprisingly, no bugs arise from that but it makes for hard to read code.

Data structures, where do I start? There’s only arrays and they are not even proper arrays. There are several “nice” features I wanted to implement and couldn’t. Sure, there are hacks like the above return trick but ain’t nobody got time for that.

Flat file is not a good replacement for a database

For me, the thing that sets redo apart from many other build tools is its use of a central database.

It records file hashes, build status and metadata in this database.

Using only shell script and common Unix tools, I implemented this database using the filesystem.

For every targets (e.g: a/b/c), there is a folder under .redo (e.g: .redo/db/a/b/c).

Inside, there are several files (e.g: checksum, dependencies…) to store metadata.

Writing is basically echo and reading is basically cat.

It sort of works.

For more complicated cases when a target is a directory, it gets … complicated.

Most of my time was spent debugging db access and how it gets corrupted.

A complicated directory tree is also hard to inspect.

Redo itself is not without problem

What I missed the most from GNU make is the use of wildcard rules.

In redo, this is done using default.do files and a simple build script search algorithm.

When redo a/b/c.one.two is called, it searches for several scripts in the following order:

- a/b/c.one.two.do

- a/b/default.one.two.do

- a/b/default.two.do

- a/b/default.do

- a/default.one.two.do

You get the idea. First, target-name.do is searched.

If that’s not found, it searches for “more generic” build scripts in the same directory.

Then it goes back up to the parent directory and repeat the process.

This allows the user to write a generic build script for multiple files (e.g: default.o.do to compile .c files).

One can still write more specific build scripts for specific files (e.g: the source file that generate a precompiled header needs different flags than the rest).

There are several problems with this:

- Build rules can only match on extension. Most of the time it’s not a problem. However, for things like linux-executables or (generated) directories, one had to add an extension just to make it work.

- Build scripts must be placed at the target site. This is because redo searches for build script at the target’s location first. Back up one directory and use “default.do”? Now your “bin” directory is two level deep: one for rules and one for actual output.

- What about output in a generated directory? Do I generate/copy a build script there? When you need to write code that writes code that writes code, it’s going to be a mess soon.

Just for fun, behold my “bin” directory:

bin

├── android

│ ├── assets

│ ├── default.apk.build.do

│ ├── default.apk.do

│ ├── default.so.build.do

│ ├── release.apk

│ ├── release.apk.build

│ └── release.so.build

├── assets.lst

├── assets.lst.do

├── create-build.sh

├── default.def.sc.do

├── default.do

├── default.fsh.do -> shaderc.od

├── default.png.do

├── default.vsh.do -> shaderc.od

├── emscripten

│ ├── assets

│ ├── build.od

│ ├── debug.do -> build.od

│ ├── default.build.do

│ ├── release

│ ├── release.build

│ ├── release.do -> build.od

│ └── shell.html

├── linux

│ ├── assets

│ ├── build.od

│ ├── default.build.do

│ ├── release.build

│ ├── shaders

│ ├── simi-debug.do -> build.od

│ └── simi-release.do -> build.od

├── shaderc

├── shaderc.do

└── shaderc.od

This is how a project using Javascript, C/C++, GLSL which must be built on Linux, Android and Emscripten (web) looks like.

Intermediate output directories (e.g: release.build and debug.build) must have extensions.

Symlinks are used as a form of code duplication reuse, how else can you apply a rule to multiple targets?

redo differentiates itself from make by storing metadata in an opaque database, independent of the build/source tree and the filesystem.

Yet, its build rules are tied to the filesystem and as a result, becomes less flexible (you can’t have “funny” characters in a file name).

I find this somewhat ironic.

What’s next (or how to redo the redone redo)?

Rewrite redo in Python 2

I think I’m done with shell script. It was a nice exercise in minimalism and pushing the limits but I can’t write anything more complicated in shell script. I overrated portability of shell scripts anyway. Python 2 is installed by default in many Linux distros and even Mac OS. It can certainly be installed on Windows.

It will still be a single file script though. Busybox, stb’s libraries, Google’s Go and my own redo implementation convinced me that the best way to deploy something simple is to make it a single file and copy paste.

SQLite as the database

Now that I have moved to Python, there’s no reason not to use a proper database. SQLite is good enough and it does not require any other libraries. Sometimes the “bloated-ness” of Python is actually a good thing [^6].

Path should be a datatype

A build tool has to manipulate paths a lot. It’s often tempting to treat them as strings. With relative paths and “..”, there are many ways to express the same path. Sure, there is a canonical form: absolute path but it’s not suitable for storing in the database. What happens if you move the project to a different folder?

Printing a path in logs is also a problem. Absolute paths are too verbose. Relative paths are nicer but relative to what? For a log, ideally it should be to the log file/project file. However, in redo, for portability of directories and scripts relative paths are always considered relative to the calling build script (which maybe a subfolder).

All these means a path can have an internal representation (absolute path for comparision), an ser-friendly representation for logging and a serializable representation for writing to the database. The build language in nix treats paths as a separate datatype from strings too. They may have encountered the same problems.

Live rebuild

With full information on the dependency graph as shown above, I could write something using inotify and automatically rebuild targets when source changes.

It should come as a separate program and not built into redo itself (redo-live?)

Having the database in a well-known format as SQLite also helps to integrate it with other tools.

A new redo-with command

This is the equivalent of make’s wildcard rule.

redo-with <script> <pattern> will register a script for a given pattern.

How will patterns be sorted?

Where to put redo-with?

I have no idea yet.

Final notes

Writing redo was a fun exercise.

It’s one of the few “experiments” that actually turns into an useful tool that I actually use myself.

-

One project requires both Java (gradle) and C/C++ (cmake). There are 3 .so outputs. They must be built for Android 4.1 and 4.4 using two different sets of android-core headers. This is because unlike the regular Java API, android-core API changes quite frequently with no backward-compatibility at all. [^2]: I did create one such build tool in the past. Even though it’s framework specific, it saved me a huge amount of time. [^3]: At start up, it creates a

.redodirectory at the project’s root and creates several symlinks with different names to itself. Build scripts are run with this directory prepended toPATHso there’s no need to modify your environment. A simple./redois enough to start a build. [^4]: Two of them are for a clients so it can’t be open sourced :(. The other one is a my own messy exploration with building web and mobile game using C++. [^5]: During development, there was a bug that makes it delete some source files. Current version is very conservative and prefer to leave some targets undeleted rather than deleting source files. [^6]: For scripting, my favourite language is Lua. It’s built for embedding and contains a very small standard library which can even be omitted. Python always comes across to me as a standalone language rather than an embedded one. ↩